- What Is Santería? A Beginner’s Guide to the Orishas and Ritual Tools

- Introduction to Santería

- The Origins and History of Santería

- Key Beliefs and Practices

- The Importance of Orishas in Santería

- Understanding the Orishas

- What Are Orishas?

- The Role of Orishas in Daily Life

- How Are Orishas Connected to Nature and Humanity?

- Exploration of Key Orishas

- Eshu: The Guardian of the Crossroads

- Oshun: The Goddess of Love and Rivers

- Shango: The God of Thunder and Lightning

- Ritual Tools and Their Significance

- The Essential Tools in Santería Rituals

- How Ritual Tools Connect Worshippers with Orishas

- The Use of Ancestor Shrines and Altars

- The Global Influence of Santería

- The Expansion of Santería Beyond the Caribbean

- Santería in Contemporary Culture

- Challenges Facing Modern Practitioners

- Frequently Asked Questions About Santería

- How Does Santería Compare to Other Religions?

- Is Santería Practiced in New Forms Today?

- What Role Does Community Play in Santería?

- Conclusion

- Summary of Key Points

- The Importance of Understanding Santería

Introduction to Santería

Santería, also known as Regla de Ocha, represents one of the most significant syncretic religious traditions to emerge from the cultural crucible of colonial Cuba. This spiritual practice, with its intricate cosmology and vibrant rituals, continues to thrive throughout the Americas and beyond, serving as a testament to the resilience of African religious traditions in the face of historical adversity.

The Origins and History of Santería

The genesis of Santería lies in the tragic circumstances of the transatlantic slave trade, which forcibly transported millions of Africans to the Americas between the 16th and 19th centuries. Among these were the Yoruba people of present-day Nigeria, Benin, and Togo, who brought with them their sophisticated religious system centered around the worship of deities known as Orishas. In Cuba, these enslaved individuals faced tremendous pressure to abandon their ancestral practices and convert to Catholicism.

Rather than relinquishing their spiritual heritage, however, the Yoruba people developed a remarkable adaptive strategy. They engaged in a process of religious syncretism, outwardly venerating Catholic saints while secretly maintaining their devotion to the Orishas by establishing correspondences between these two pantheons. This ingenious approach allowed the Lukumí (Cuban Yoruba) to preserve their cosmological framework and ritual practices while appearing to conform to the dominant religious paradigm.

"Santería emerged as a profound act of spiritual resistance and cultural preservation during one of history's darkest chapters. Its very existence speaks to the indomitable human spirit and the power of faith to transcend oppression."

Key Beliefs and Practices

At its theological core, Santería posits a supreme creator deity called Olodumare who, while transcendent, remains somewhat distant from human affairs. The Orishas, as manifestations of divine energy (ashé), serve as intermediaries between humanity and this ultimate godhead. Practitioners cultivate reciprocal relationships with these deities through elaborate ceremonies, offerings, and the observance of specific taboos and prescriptions.

Central to Santería practice is the concept of divination, particularly through systems such as the Diloggún (cowrie shell divination) and Ifá (palm nut divination). These methods enable communication with the Orishas and ancestors, providing guidance for navigating life's complexities. Initiation rituals, known as kariocha or "making the saint," establish formal covenants between devotees and their patron Orishas, often involving elaborate ceremonies spanning multiple days.

The ceremonial calendar of Santería includes numerous festivities honoring specific Orishas, featuring drumming, dancing, and sacrificial offerings that create powerful communal experiences. Music plays a particularly significant role, with the batá drums serving as sacred instruments believed to literally "speak" the language of the Orishas through complex polyrhythmic patterns.

The Importance of Orishas in Santería

The Orishas constitute the central focus of devotional practice in Santería. Each Orisha embodies distinct cosmic forces, personality traits, and domains of influence within the natural world. Practitioners often discover their spiritual affinity with particular Orishas through divination, establishing lifelong connections that shape their religious identity and ritual obligations.

Within the spiritual ecosystem of Santería, certain tools and implements serve as material conduits for invoking and honoring the Orishas. These sacred objects become repositories of ashé, the vital spiritual energy that animates the universe. For those drawn to connect with specific Orishas, properly consecrated ritual items can facilitate deeper spiritual communion.

For devotees of Oshun, the beloved Orisha of rivers, fertility, and love, specific emblems and offerings hold particular significance. Her association with sweetness, beauty, and abundance makes her one of the most widely venerated deities in the Santería pantheon.

Among the most authentic expressions of devotion to Oshun are specially crafted ritual items that incorporate her sacred symbols and materials. These items serve not merely as decorative accessories but as spiritually potent tools for establishing connection with this powerful feminine deity.

The Pulsera de Oshun represents an exemplary embodiment of traditional craftsmanship aligned with authentic spiritual purpose. This bracelet, meticulously handcrafted with cowrie shells and bronze elements, channels the essence of Oshun's energy through materials traditionally associated with her domain.

The bracelet's incorporation of cowrie shells—historically used as currency and divinatory tools in West Africa—connects the wearer to ancient traditions while the golden bronze elements reflect Oshun's association with honey, wealth, and the sun's radiance. For practitioners seeking to honor this Orisha or to benefit from her protective and prosperity-bringing qualities, such traditional, handcrafted items provide a tangible connection to her divine presence.

Understanding the Orishas

What Are Orishas?

The Orishas represent divine manifestations of Olodumare's (Supreme Creator's) energy in the Yoruba spiritual cosmology. Unlike the Western conception of gods, Orishas embody multifaceted aspects of both natural phenomena and human characteristics, existing as complex archetypes rather than simplistic deities. Each Orisha manifests a unique combination of virtues, flaws, and abilities that mirror the complexity of human experience.

The term "Orisha" itself derives from the Yoruba language, combining "ori" (head/consciousness) and "sha" (to select), suggesting entities that select human consciousness as vessels for divine expression. This etymology reflects the profound belief that Orishas may occasionally "mount" or possess their devotees during ceremonial contexts, temporarily inhabiting their bodies to communicate directly with the community.

Numerologically, the Lucumí tradition traditionally recognizes seven primary Orishas—Elegguá, Obatalá, Yemayá, Changó, Ochún, Oyá, and Oggún—though the complete pantheon comprises hundreds of deities. Each primary Orisha further divides into numerous "caminos" or paths, representing different aspects or manifestations of their essential nature.

The Role of Orishas in Daily Life

Far from being distant figures of worship, Orishas actively participate in the quotidian existence of their devotees. Practitioners cultivate intimate, familial relationships with these deities, consulting them for guidance, protection, and intervention in mundane affairs. This relationship dynamic more closely resembles that of extended family members than the remote adoration common in some other religious traditions.

Devotees often discover their spiritual affinity with specific Orishas through divination, establishing what is known as their "guardian angel" or tutelary deity. This connection influences numerous aspects of daily practice, from dietary restrictions to color preferences and behavioral guidelines. The relationship between devotee and Orisha evolves throughout one's lifetime, deepening through consistent ritual attention and offerings.

| Orisha | Domain | Colors | Offerings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Elegguá | Crossroads, fate, opportunity | Red and black | Candy, cigars, rum |

| Oshun | Rivers, love, prosperity | Yellow, amber, gold | Honey,oranges, cinnamon |

| Shango | Thunder, justice, masculine power | Red and white | Apples, okra, ram |

How Are Orishas Connected to Nature and Humanity?

The Orishas embody natural forces and elements, establishing an intrinsic connection between spiritual practice and ecological awareness. Yemayá governs the oceans; Oshun presides over freshwater rivers; Shango commands thunder and lightning; Oggún rules metallurgy and technology. This intimate association with natural phenomena reflects the tradition's holistic worldview, wherein spiritual forces permeate and animate the material world rather than transcending it.

Additionally, each Orisha embodies specific aspects of human psychology and social dynamics. Oshun represents femininity, sensuality, and artistic expression; Shango embodies masculine strength, leadership, and judicial authority; Obatalá governs intellect, moral rectitude, and peace. By working with these archetypal energies, practitioners gain insight into their own psychological complexities and develop greater emotional intelligence.

This integration of natural elements and human characteristics creates a spiritual framework that addresses both environmental harmony and personal development. The devotee who honors Oshun, for example, simultaneously acknowledges the ecological importance of fresh water systems and cultivates the emotional qualities of compassion, creativity, and sensuality associated with this Orisha.

Exploration of Key Orishas

Eshu: The Guardian of the Crossroads

Eshu (also called Elegguá in Cuban Santería) occupies a singular position within the Orisha pantheon as the divine messenger and cosmic trickster who mediates between the human and divine realms. As guardian of the crossroads—both literal and metaphorical—Eshu embodies the principle of potentiality that exists at every junction, decision point, and threshold. His domain encompasses fate, chance, opportunity, and the unexpected vicissitudes of existence.

Iconographically, Eshu appears with multiple visages reflecting his multidimensional nature. He may manifest as a mischievous child, a virile young man, or an elderly sage depending on which "camino" or aspect is being addressed. His traditional representation often features a cement head with cowrie shells forming eyes and mouth, adorned with red and black beads symbolizing the dualities he transcends. The asymmetrical nature of many Eshu statues visually reinforces his ability to simultaneously inhabit multiple realms.

Linguistically, Eshu's name derives from the Yoruba term "èṣù," denoting sphere or globe, suggesting his omnipresence and capacity to traverse all dimensions. In Santería cosmology, Eshu serves as the indispensable intermediary without whom no communication between humans and other Orishas can occur. This primordial positioning necessitates that he receive the first offering in any ceremony.

Devotional practices honoring Eshu typically begin with propitiation, acknowledging his preeminent role as divine gatekeeper. Practitioners traditionally place his shrine near the entrance of homes or temples, reflecting his association with thresholds and boundaries. Ceremonial protocols dictate that Eshu receives the first libation (mojiganga) in any ritual sequence, regardless of which Orisha constitutes the primary focus of worship.

Eshu's preferred offerings include candies (particularly red and black varieties), cigars, rum, palm oil, and small toys reflecting his playful nature. Devotees often leave these items at crossroads, railroad tracks, or other intersections that symbolize his domain. The number three holds special significance in Eshu worship, with offerings frequently arranged in triads or presented on the third day of the week.

During possession ceremonies, Eshu's arrival manifests through distinctive behavioral patterns: the deity typically enters dancing energetically, performing mischievous antics, speaking in riddles, and occasionally engaging in provocative or boundary-testing behaviors. These manifestations reflect his role as divine trickster who challenges social conventions and disrupts calcified patterns of thought.

Oshun: The Goddess of Love and Rivers

Oshun (Ochún in Spanish orthography) embodies the archetypal feminine principle in its most enchanting and beguiling manifestations. As sovereign of fresh waters—particularly rivers—she governs domains including love, fertility, prosperity, diplomacy, and artistic expression. Oshun's mythology portrays her as the youngest yet most beloved daughter of Olodumare, possessing unparalleled beauty that grants her exceptional persuasive power even among the Orishas.

The material emblems associated with Oshun include honey (symbolizing sweetness and the power to attract), amber (representing her golden radiance), peacock feathers (denoting her beauty), mirrors (reflecting her association with self-awareness), fans (suggesting her coquettish nature), and pumpkins (acknowledging her connection to fertility and abundance). Her sacred number five corresponds to the five rivers in Yorubaland associated with her worship.

Chromatically, Oshun associates primarily with yellow, amber, coral, and gold—colors that evoke sunshine, honey, and prosperity. Her devotees often wear these hues, particularly on her sacred day (Saturday). The sensorial aspects of Oshun worship emphasize sweetness, beauty, and sensuality across multiple modalities: fragrant perfumes, melodious music, graceful dance, and delectable foods.

Annual celebrations honoring Oshun include elaborate processions to riverbanks where offerings of honey, sunflowers, pumpkins, and sweet foods are ceremonially presented. The most renowned of these observances occurs at the Osun-Osogbo Sacred Grove in Nigeria (a UNESCO World Heritage site) and at the Virgen de la Caridad del Cobre shrine in Cuba, where Oshun syncretizes with this Catholic manifestation of the Virgin Mary.

Ritual implements utilized in Oshun ceremonies include brass or gold vessels containing river water, honey pots, hand-fans adorned with her symbols, and her signature metal implements (tools) decorated with bells that produce tinkling sounds reminiscent of flowing water. Her altar typically features a yellow cloth, a mirror, honey, perfumes, and objects representing wealth and beauty.

In possession ceremonies, Oshun's arrival manifests through graceful, sensual dancing characterized by undulating movements evoking flowing water. When "mounting" a devotee, she typically displays coquettish behavior, admires herself in mirrors, distributes honey to attendees, and offers prophetic insights delivered with maternal compassion rather than stern pronouncements.

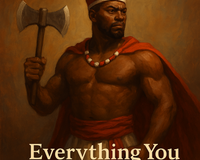

Shango: The God of Thunder and Lightning

Shango (Changó in Cuban orthography) personifies masculine potency in its most commanding aspects, governing thunder, lightning, fire, drums, dance, and virility. Historical accounts identify him as the deified fourth king of the ancient Oyo Empire, whose posthumous elevation to Orisha status reflects his extraordinary impact during his mortal existence. His archetypal persona embodies the paradoxical fusion of destructive power and creative force inherent in electrical phenomena.

Visually, Shango appears as a regal warrior bearing a double-headed axe (oshe) that symbolizes the lightning bolts he hurls from the heavens. His iconic representation includes six thunderstones (meteorite fragments believed to be physical manifestations of lightning strikes) arranged in a specific pattern. Red and white constitute his primary colors, representing fire and moral purity respectively.

Shango's mythological narratives portray him as a complex figure who embodies both admirable qualities (courage, leadership, charisma) and cautionary flaws (impetuosity, excessive pride, hedonism). These multifaceted attributes render him particularly relevant for devotees navigating the challenges of power, authority, and ethical leadership in contemporary contexts.

As divine arbiter of justice, Shango presides over ceremonies addressing legal disputes, social conflicts, and ethical transgressions. His intervention is sought when human adjudication proves insufficient or corrupt. These justice-oriented rituals often involve the rhythmic invocation of his presence through specific batá drum patterns known as "toques de Changó" that replicate the sonorous qualities of thunder.

- Judicial ceremonies request Shango's discernment in complex moral situations

- Protection rituals invoke his fierce guardianship against enemies

- Leadership empowerment ceremonies channel his authoritative presence

- Fertility rites harness his virile, generative energies

Shango's sacred implements include the oshe (double-headed axe), bata drums, wooden vessels painted red and white, and carved representations of ram's horns signifying his formidable will. His altar typically

Ritual Tools and Their Significance

The Essential Tools in Santería Rituals

The material culture of Santería encompasses a sophisticated array of ritual implements, each possessing specific functions and symbolic resonances within ceremonial contexts. These sacred tools, collectively termed "herramientas," serve as conduits for ashé (divine energy) and facilitate communication between devotees and the Orishas. Unlike mass-produced religious paraphernalia, authentic Santería implements require proper consecration through specific ceremonial protocols to activate their spiritual efficacy.

Among the most fundamental ritual tools are the elekes (beaded necklaces), which devotees receive during preliminary initiation ceremonies. Each eleke features a distinctive color pattern corresponding to a specific Orisha, with the beads arranged in precise configurations that encode spiritual information. These necklaces serve multiple functions: they identify the wearer's spiritual affiliations, provide protective energies, and establish a material connection to the Orisha whose colors they bear.

Equally significant are the various forms of ritual implements known as herramientas de Ocha, which include:

- Soperas (tureens) - Consecrated vessels that house the sacred stones (otanes) representing each Orisha's physical presence

- Iruke (horse-tail whisk) - Used for ritual purification and to disperse negative energies

- Ildé (metal bracelet) - Worn as a protective emblem of one's patron Orisha

- Matipó (chalk) - Employed for drawing sacred symbols (firmas) that invoke specific spiritual forces

- Diloggún (cowrie shells) - Utilized as divination implements to communicate with Orishas

The acquisition and maintenance of these implements entail specific protocols and taboos. Many items require periodic "feeding" with offerings appropriate to their associated Orisha, while others demand particular storage conditions or handling practices. The interrelationship between these various tools creates a coherent material system that externalizes the tradition's cosmological principles.

How Ritual Tools Connect Worshippers with Orishas

The ontological status of ritual implements in Santería transcends mere symbolism; these objects function as tangible access points to numinous realities. Through processes of consecration, ordinary materials undergo metaphysical transformation, becoming what scholars term "theophanic objects"—physical items that manifest divine presence. This transformation occurs through elaborate ceremonial procedures involving specific incantations, offerings, and the transfer of ashé from established sacred objects to newly created ones.

The efficacy of ritual tools depends upon their embeddedness within proper ceremonial contexts and their manipulation by individuals possessing the requisite spiritual authority. Initiated priests (santeros/santeras) and priestesses who have undergone the kariocha ceremony possess the spiritual standing to activate these implements' latent potentialities. Their ritual knowledge, transmitted through oral tradition and practical apprenticeship, enables the proper deployment of these sacred technologies.

Different categories of ritual implements facilitate distinct modes of communion with the Orishas:

Divinatory tools like the diloggún (cowrie shells) and ekuele (divination chain) enable practitioners to receive spiritual guidance and interpret the Orishas' messages regarding personal decisions, spiritual development, and ritual requirements. These implements function as oracular interfaces, translating divine wisdom into systematized patterns that trained diviners can interpret.

Sacrificial implements such as the pinaldo (ritual knife) and various vessels for offerings facilitate the exchange of vital energies between devotees and Orishas. Through properly conducted sacrificial rituals, practitioners establish reciprocal relationships with divine forces, offering life-energy in exchange for spiritual blessings, guidance, and protection.

Devotional implements like beaded necklaces (elekes), bracelets (ildés), and consecrated stones (otanes) provide continuous channels for spiritual connection, allowing practitioners to maintain ongoing relationships with their tutelary deities outside formal ceremonial contexts. These items, worn on the body or maintained on personal altars, serve as constant reminders of one's spiritual commitments and sources of protective energy in daily life.

The Use of Ancestor Shrines and Altars

Central to Santería practice is the establishment and maintenance of sacred spaces that house the spiritual forces with which practitioners interact. These consecrated areas range from elaborate community temples (ilé ocha) to modest household shrines dedicated to specific Orishas or ancestral spirits. The spatial organization of these sacred sites reflects the tradition's cosmological principles, with distinct areas allocated to different categories of spiritual entities.

The bóveda espiritual (spiritual table) constitutes the foundational ancestral shrine in most practitioners' homes. This altar typically features a white tablecloth, clear glasses of water, white candles, flowers, and photographs or mementos of deceased family members. The bóveda serves as a locus for communion with one's egun (ancestors), who are considered essential intermediaries between the living and the Orishas. Regular offerings of water, prayers, and tobacco smoke maintain these ancestral connections.

Orisha-specific altars exhibit distinctive characteristics reflecting each deity's attributes:

Elegguá's shrine typically resides behind the front door, featuring a cement head with cowrie shells forming facial features, placed on a terracotta plate with offerings of candy, cigars, and rum. This placement acknowledges his role as divine messenger and guardian of thresholds.

Oshun's altar usually incorporates a yellow cloth, brass or gold vessels containing river water, honey pots, pumpkins, peacock feathers, and mirrors. The aesthetic emphasizes beauty, sweetness, and sensuality, reflecting her domains of influence.

Shango's shrine typically features a wooden vessel (batea) painted red and white, containing his thunderstones (meteorite fragments), double-headed axe (oshe), and offerings of apples, red palm oil, and ram's horns. The arrangement conveys masculine strength and royal authority.

The maintenance of these sacred spaces involves regular cleaning, refreshing of offerings, and observance of specific protocols regarding who may approach or touch various components. Many altars incorporate layers of esoteric symbolism visible only to initiated practitioners, creating a hierarchical system of access to spiritual knowledge that reinforces the tradition's initiatory structure.

The Global Influence of Santería

The Expansion of Santería Beyond the Caribbean

The geographical diffusion of Santería beyond its Cuban crucible represents one of the most significant religious diasporas of the 20th century. This expansion occurred through multiple vectors, including political exile, economic migration, cultural exchange, and deliberate evangelization efforts. The most substantial dispersion began with the Cuban Revolution of 1959, which precipitated waves of emigration primarily to the United States, particularly to Florida, New York, and New Jersey, creating vibrant centers of Lukumí practice in these regions.

Subsequent migration patterns extended Santería's presence throughout the Americas, with substantial communities emerging in Venezuela, Colombia, Mexico, and Brazil. These demographic movements facilitated cross-fertilization with cognate traditions such as Brazilian Candomblé, Haitian Vodou, and Dominican Las 21 Divisiones, generating new syncretic expressions while maintaining core theological and ritual principles.

The late 20th century witnessed Santería's transatlantic journey to Europe, particularly to Spain, Germany, and Italy, where Cuban diaspora communities established religious centers. This reverse migration created the intriguing phenomenon of African-derived spiritual practices returning to European soil, challenging conventional narratives about religious diffusion and cultural influence.

Contemporary globalization processes, including digital communication technologies and increased international travel, have accelerated Santería's worldwide dispersion. Online forums, social media platforms, and video-sharing sites now facilitate knowledge transmission and community building across national boundaries, though many practitioners express concern about the potential dilution of tradition through decontextualized information sharing.

Santería in Contemporary Culture

The cultural footprint of Santería extends far beyond explicitly religious contexts, permeating various aspects of contemporary artistic expression, popular culture, and intellectual discourse. Musical genres including Latin jazz, salsa, and hip-hop frequently incorporate references to Orisha mythology and ritual elements, with artists like Celia Cruz, Mongo Santamaría, and The Orishas explicitly drawing inspiration from this tradition.

Literary works by authors such as Lydia Cabrera, Cristina García, and Junot Díaz have introduced Santería concepts to international readerships, while visual artists including José Bedia, Ana Mendieta, and María Magdalena Campos-Pons have incorporated Lukumí iconography and philosophical principles into their creative oeuvres. These artistic interpretations function simultaneously as cultural preservation efforts and innovative recontextualizations of traditional elements.

The cinematic representation of Santería has evolved from exoticized portrayals in films like "The Believers" (1987) to more nuanced depictions in works such as "Santería: The Soul Possessed" (2011) and "Patakí" (2015). Contemporary filmmakers increasingly consult with religious authorities to ensure accurate representation, reflecting growing cultural sensitivity regarding the tradition's portrayal.

Academic engagement with Santería has similarly transformed, moving from early anthropological approaches that often pathologized practices as "primitive survivals" toward more respectful scholarly frameworks that recognize the tradition's theological sophistication and cultural significance. University courses on African diaspora religions, comparative religious studies, and ethnomusicology now regularly include substantive treatment of Santería.

Challenges Facing Modern Practitioners

Contemporary adherents of Santería navigate complex challenges arising from the tradition's intersection with modernity, legal frameworks, environmental concerns, and internal doctrinal debates. Legal obstacles persist in numerous jurisdictions, particularly regarding animal sacrifice—a core ritual practice protected in the United States by the landmark Supreme Court case Church of the Lukumi Babalu Aye v. City of Hialeah (1993), but still contested in other regions.

Environmental pressures impact traditional practices in multiple ways. The collection of certain plants, minerals, and animal species used in rituals faces increasing restrictions due to conservation concerns. Urbanization has reduced access to natural spaces traditionally used for ceremonies, while water pollution compromises the quality of river water essential for rituals honoring Oshun and other water-associated Orishas.

Internal debates regarding authenticity, innovation, and authority structures generate significant tensions within practitioner communities. The absence of a centralized ecclesiastical hierarchy permits diverse interpretations and practices, creating what scholars term "orthopraxy" (correct practice) rather than "orthodoxy" (correct belief). Questions surrounding legitimate adaptation versus inappropriate dilution arise particularly regarding:

- The appropriate extent of technological integration (e.g., digital divination, online rituals)

- Proper protocols for initiating non-Cuban or non-African practitioners

- The status of LGBTQ+ individuals within traditional gender-differentiated ritual roles

- Appropriate commercial practices related to spiritual services and ritual implements

Commercialization presents particular challenges, as increased market demand for ritual items has spawned mass-produced alternatives to traditionally crafted implements. Discerning practitioners increasingly seek authentic, ethically sourced items created by knowledgeable artisans who understand the spiritual principles underlying their design and fabrication.

Frequently Asked Questions About Santería

How Does Santería Compare to Other Religions?

Santería exhibits both convergent and divergent elements when juxtaposed with other major religious traditions. Unlike monotheistic faiths such as Christianity, Judaism, and Islam, which emphasize exclusive devotion to a single deity, Santería acknowledges a supreme creator (Olodumare) while focusing devotional practice on multiple divine manifestations (Orishas). This theological structure more closely resembles Hindu approaches to divinity than Abrahamic monotheism.

Ritual emphasis constitutes another significant distinction. While many contemporary religions prioritize textual study, ethical precepts, or personal faith, Santería centers efficacious ritual action as the primary mode of religious engagement. This emphasis on orthopraxis (correct practice) rather than orthodoxy (correct belief) aligns it with traditions like Shinto, certain forms of Buddhism, and other indigenous spiritual systems.

The initiatory structure of Santería, with its progressive levels of ritual knowledge and authority, parallels aspects of Mystery traditions such as ancient Eleusinian rites, Mithraism, and contemporary Wiccan covens. This hierarchical organization of spiritual knowledge contrasts with the more egalitarian approaches to religious information found in many Protestant denominations and New Age spiritualities.

Unlike religions that emphasize transcendence of material reality or postponement of rewards to an afterlife, Santería exhibits pronounced this-worldly concerns, addressing practical matters such as health, prosperity, relationships, and protection. This pragmatic orientation resembles Chinese folk religion and various indigenous American spiritual systems.

Is Santería Practiced in New Forms Today?

Contemporary manifestations of Santería demonstrate remarkable adaptability while maintaining core principles. Several notable evolutionary trajectories have emerged in recent decades, reflecting the tradition's dynamic engagement with changing social contexts:

Technological integration represents perhaps the most visible innovation, with practitioners utilizing digital platforms for educational outreach, community building, and even certain forms of ritual participation. Virtual bembés (drumming ceremonies) during the COVID-19 pandemic exemplified this adaptive capacity, though debate continues regarding which elements of practice can legitimately transition to digital formats.

Environmentally conscious adaptations have emerged in response to ecological concerns and resource limitations. Some practitioners now substitute synthetic materials for endangered species traditionally used in certain rituals, while others develop ceremonial modifications that maintain spiritual efficacy while reducing environmental impact.

Feminist reinterpretations have gained prominence, challenging historically patriarchal elements within the tradition. Female religious leaders increasingly reclaim and amplify the roles of women in Santería's historical development, while developing liturgical innovations that enhance gender equity without compromising ritual effectiveness.

Intellectual engagement with academic disciplines including psychology, ecology, and quantum physics has generated sophisticated theological articulations that position Santería's concepts within contemporary intellectual frameworks. These interdisciplinary conversations produce what religious studies scholars term "reflexive traditionalism"—conscious maintenance of traditional forms informed by critical engagement with modernity.

What Role Does Community Play in Santería?

The communal dimension of Santería constitutes not merely an adjunct aspect but a fundamental theological principle. The concept of ilé (religious family/house) provides the essential organizational structure within which spiritual development occurs. Unlike religions that emphasize individual salvation or personal enlightenment, Santería situates religious identity firmly within a network of reciprocal relationships—both human and divine.

The initiation process explicitly creates ritual kinship bonds, with initiates receiving spiritual "godparents" (padrinos/madrinas) who assume responsibility for their religious education and well-being. These relationships mirror biological family structures but often surpass them in emotional significance and practical support. The godparent-godchild relationship establishes lineages that practitioners can trace through generations, connecting contemporary adherents to historical figures in the tradition.

Ceremonial activities reinforce community cohesion through collective participation in drumming, dancing, feast preparation, and ritual construction. Major ceremonies require the coordinated efforts of numerous specialists, creating interdependence that transcends individual spiritual concerns. Even seemingly personal rituals typically involve multiple community members, reinforcing the notion that spiritual development occurs within social contexts rather than in isolation.

Mutual aid networks among practitioners provide practical assistance during life transitions, health crises, and economic difficulties. These support systems often operate according to religious principles rather than secular logics, with resource distribution guided by divination and spiritual considerations alongside practical needs assessment.

Conclusion

Summary of Key Points

Throughout this exploration of Santería, we have traversed the complex historical, theological, and ritual landscapes that constitute this profound spiritual tradition. From its origins in the crucible of colonial oppression to its contemporary global manifestations, Santería demonstrates remarkable resilience, adaptability, and spiritual depth. Several essential characteristics distinguish this tradition:

Its syncretic nature represents not mere religious conflation but a sophisticated strategy of cultural preservation and resistance. By establishing correspondences between Yoruba Orishas and Catholic saints, practitioners maintained their ancestral spiritual framework while navigating hostile social environments—a testament to human ingenuity in preserving sacred knowledge under adverse conditions.

The centrality of the Orishas—Eshu guarding crossroads and possibilities, Oshun embodying love and prosperity, Shango wielding thunder and justice—provides a theological framework that addresses both cosmic forces and human psychological dimensions. These divine archetypes offer practitioners multifaceted models for understanding both natural phenomena and personal development.

The material culture of Santería, with its elaborate ritual implements, sacred objects, and altar configurations, creates tangible connections between devotees and spiritual forces

The material culture of Santería, with its elaborate ritual implements, sacred objects, and altar configurations, creates tangible connections between devotees and spiritual forces. These ritual tools—from beaded necklaces to divination implements—serve not merely as symbols but as active conduits for ashé, the vital spiritual energy that animates religious practice.

The community-centered nature of Santería distinguishes it from more individualistic spiritual approaches. Through ritual kinship networks, collective ceremonies, and shared responsibilities, the tradition fosters deep social bonds that support practitioners through life's challenges while creating contexts for authentic spiritual experience.

The tradition's continued evolution demonstrates its living character, as practitioners navigate contemporary challenges while maintaining core principles. Technological adaptations, environmental consciousness, and engagement with modern intellectual frameworks exemplify Santería's dynamic responsiveness to changing conditions.

The Importance of Understanding Santería

Cultivating accurate knowledge about Santería serves multiple significant purposes that extend beyond mere academic interest. For potential practitioners, authentic information provides necessary foundations for respectful engagement with a tradition that requires proper guidance and initiation. Without accurate understanding, individuals risk both spiritual missteps and cultural appropriation.

For the broader public, nuanced comprehension of Santería contributes to religious literacy and intercultural appreciation in increasingly diverse societies. Dispelling persistent misconceptions—particularly those rooted in colonial-era prejudices or sensationalistic media portrayals—advances social justice by countering discrimination against practitioners.

From an academic perspective, Santería offers valuable insights into human resilience, cultural adaptation, and religious creativity. The tradition's history demonstrates how marginalized communities preserve spiritual heritage despite oppressive conditions, while its contemporary manifestations illustrate religion's dynamic engagement with modernity.

For practitioners of other spiritual paths, Santería presents alternative paradigms for conceptualizing human-divine relationships, ritual efficacy, and community formation. Its emphasis on embodied knowledge, direct spiritual experience, and practical outcomes offers valuable counterpoints to more text-centered or abstractly theological approaches.

Perhaps most significantly, Santería preserves profound philosophical and ecological wisdom from African traditions that might otherwise have been lost to history. Its understanding of the interconnectedness of natural forces, human consciousness, and divine energy resonates with contemporary ecological concerns and holistic approaches to well-being.

As the global community continues to grapple with challenges of environmental sustainability, social cohesion, and spiritual meaning, traditions like Santería offer valuable resources for reimagining human relationships with both natural and social ecosystems. By approaching this tradition with respect and openness, we access not only fascinating cultural knowledge but potentially transformative wisdom for navigating our collective future.

Those drawn to deeper engagement with this tradition would do well to seek authentic sources of knowledge, preferably through established practitioners who understand both the spiritual principles and cultural contexts of these practices. The journey into Santería begins, appropriately enough, at the crossroads of cultures—where respectful curiosity meets authentic tradition, creating possibilities for meaningful spiritual connection across historical and cultural boundaries.